cities around the world, but especially in asiaAccording to a new study published in Biology, these organisms are moving upwards more rapidly than they are spreading outwards. Nature City found. In a world moving towards rapid urbanisation, tall buildings can accommodate more people in less space, but they can also negatively impact existing infrastructure, the local environment and even the climate.

“The urban population has increased by about 2 billion people from 1990 to 2020,” said Steven Frohling, an earth scientist at the University of New Hampshire and lead author of the current study. “So cities have had to grow to accommodate those 2 billion people. The question is, how have they grown?”

an increasing amount

A team of Earth and urban scientists came together to answer this question and observed more than 1,500 cities around the planet from the 1990s to the 2010s. They used remote-sensing satellite data to gather information about the vertical growth and two-dimensional (2D) outward spread of cities.

To understand how cities grew, the team examined their footprint: the rate at which land area was being covered by buildings. They also used data from scatterometers – satellite-borne sensors that send pulses of microwaves to the Earth’s surface and collect the data reflected back – to understand how city structures changed over time.

“So we thought that by combining these two data sets we could get a better picture of how cities are evolving laterally and vertically,” Dr Fröling said.

They found that the rate of 2D expansion was not as high: that is, cities were not expanding as much as they used to. But the microwave data showed that the size of urban structures was increasing.

‘Only paper in literature’

“The microwave data is sensitive to both lateral growth and vertical growth, but we see it growing more rapidly in most cities over the three-decade period,” Dr. Froling said. “So if cities are not accelerating at the rate of building construction, but they are increasing the volume of construction – which is what we think microwave correlates most reliably with – that means it’s vertical[growth].”

A view of Shanghai, China on January 8, 2020. | Photo Credit: Road Trip With Raj/Unsplash

Based on their analysis, the researchers found that cities around the world are experiencing upward growth, with some East Asian cities, particularly those in China, leading the way. Cities with populations over 10 million have seen more vertical growth, and this effect has become even more pronounced in the 2010s.

“This is the only paper in the literature that looks at upward growth over such a long period of time and for such a large sample of cities,” said Richa Mahatta in an email. She is a Yale graduate student along with Karen Seto, one of the world’s leading experts on the subject and a co-author of the study.

“3D urban development can open a new paradigm for remote sensing research and its applications in advancing our understanding of urban growth and its impacts on local climate,” Ms. Mehta said.

‘This is a good effort’

“Up to a certain limit, a city can grow, right? Beyond a limit, it will start getting dense,” said HS Sudhira, who has a PhD in urban planning and governance from the Indian Institute of Science, Bengaluru, and is currently the director of Gubbi Labs. “What is important from a more policy and practical perspective is to understand what is the limit at which it shifts from outward growth to being dense in such a way that it becomes vertical.”

“This is a really good attempt to look at this from a global perspective,” he said.

Indian cities have not seen a uniform upward growth, with only the larger cities with a population over 5 million experiencing upward or outward growth, mostly in the 2010s.

“Particularly in India, compared to China, cities have much more regulation on building heights. So cities in India have not been able to grow vertically as rapidly as those in East Asia or Southeast Asia,” Dr. Froling said.

For example, in Delhi, most of the growth in the 1990s and 2000s was outward, while some growth in the 2010s was upward.

‘Cities are not like naturally occurring creatures’

Surajit Chakravarty, urban planner and policy scholar at IIT Delhi (speaking personally), believes that we must be cautious before defining cities as a global trend in very diverse contexts.

“This is a very interesting paper about the morphology of cities from a comparative international perspective,” Dr. Chakravarty wrote in an email to this reporter. “But cities are not like naturally occurring creatures. Their size and shape are determined not by the laws of nature but by policies, regulations, jurisdictional boundaries, economic conditions and historical patterns. All of these are socially constructed. In addition, physical geography plays an important role.”

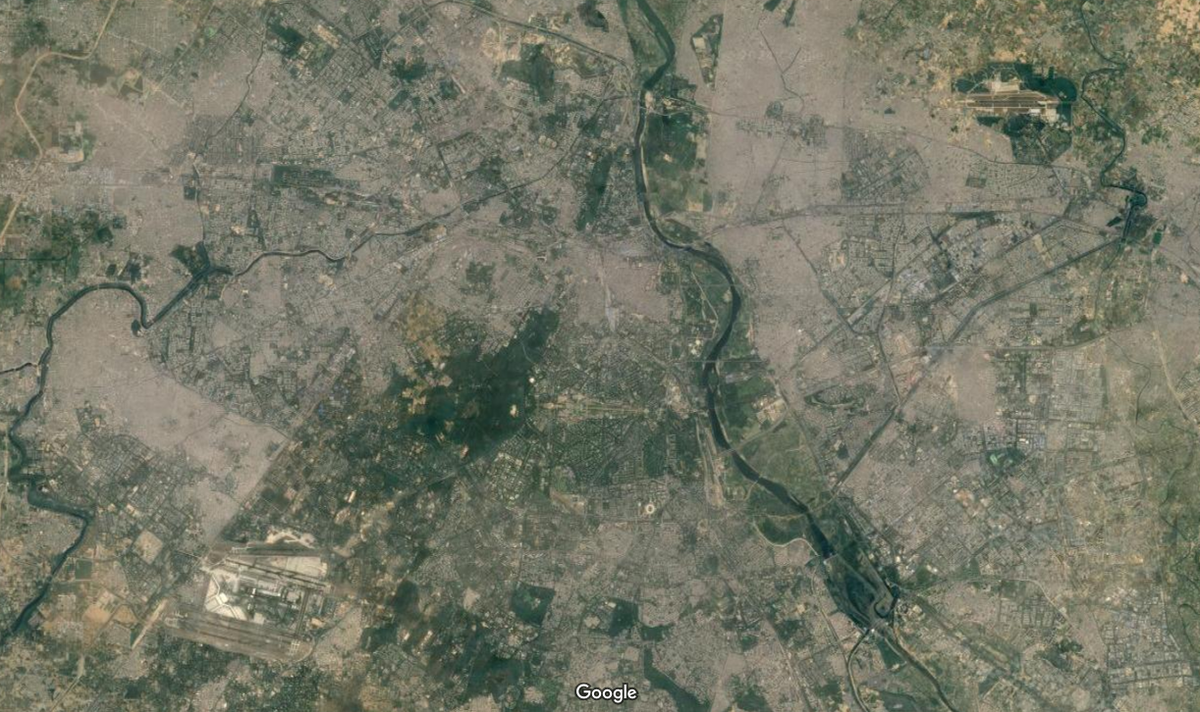

Detailing some of the rules that Dr. Froling mentioned, Dr. Chakravarti said that in some places, such as New Delhi, the most expensive central Delhi real estate – or the “Lutyens bungalow area” – is very well protected. This has led to most high-rise buildings being built on the outskirts of Delhi, for example in Noida and Gurugram. Similar heritage areas or protected areas may also exist in the central parts of many other South and Southeast Asian cities. This situation is not comparable with most cities in North America.

A panoramic view of New Delhi in 2023. | Photo credit: Google Earth

Another reason for not including some areas of Indian urbanisation in the current paper is its low resolution: the scale used in the paper is about 5 km. “This is a very low resolution for India,” said Dr Sudhira. But she acknowledged that increasing the spatial resolution for such a global study would have generated too much data that would have been too complex to analyse.

Cities are less efficient

“A large part of urbanisation in India is taking place outside the parameters of the study, through the process of transformation of very small towns and villages into urban spaces,” Dr Chakravarti said.

Vertical growth can increase population density, and if the cost is justified, can also house more people (i.e. more density). But such growth needs to be supported with more jobs and good public transport to reduce transport emissions and improve walkability. Robust infrastructure with decent sewage and water systems is also needed to sustain large numbers of people. Taller buildings will also require specialised resources and have higher energy demands.

While growth is important, how to achieve it – while keeping sustainability and climate resilience in mind – is crucial in these times of unprecedented climate change. Despite rapidly increasing rates of urbanisation, Dr Sudhira is grateful that most Indians still live in rural, dispersed settlements, which she says are more efficient and climate-resilient.

Tall buildings with no tree cover can also create an urban “heat island” effect, which can affect temperatures and rainfall in cities. Studies published On 11th June Journal of Advances in Modeling Earth Systems Studied the development of Shanghai and showed that having more built-up area could reduce wind speeds by up to half.

“It’s not as simple as saying that doing it this way is better than doing it that way. All of these things involve trade-offs,” said Dr. Froling. “We want to find a way to look at how cities are evolving, at these trajectories, and see if there are patterns that can help us predict energy and resource use. 3D urban structure has implications for many factors, including disaster relief, sustainability and liveability.”

Dated Master Plan

Firefighters evacuate residents of Rainbow Layout after the Halanayakanahalli lake breached following heavy rains, on Sarjapur Road, Bengaluru, September 5, 2022. | Photo credit: Murali Kumar K./The Hindu

“We (India) are following the path of China, at least in terms of population and to some extent in terms of industrialisation and economic growth,” said Dr Sudhira. “In that context, I would see this paper as a warning; we really need to sit down at the drawing board and say should we really allow more tall buildings and what should the policy be on this?”

Most cities and states in India, including Bengaluru, are operating with outdated master plans that determine how land will be used for various urban structures. According to Dr. Sudhira, most existing planning laws do not even acknowledge transportation, energy, water, resources, wastewater management and solid waste.

“We need to rethink and rewrite our master planning acts, and come up with a more progressive law that is enforceable and can stand the test of time,” he said. “It should include all of these things and also aspects of climate change, because I think we are in a time where you cannot ignore climate change.”

“There is no one-size-fits-all approach to cities,” said Dr Chakravarti. “India needs trained planners who can make decisions at the local level, taking into account people’s needs and aspirations, and sustainability and liveability objectives.”

Rohini Subramaniam is a freelance journalist based in Bengaluru.